Find information on how to make a Protected Disclosure under the external procedures in place in the HEA.

8. Broader Outcomes

Both nationally and internationally, reporting on graduate outcomes tends to focus on employment earnings. The HEA’s Graduate Outcomes Survey captures graduate destinations nine months post-graduation, and its focus relates mainly to employment and further studies outcomes. Data produced by the Central Statistics Office (CSO), via the Educational Longitudinal Database, is also employment-focused, linking HEA graduation records with Revenue and Social Protection administrative data. With that in mind, this chapter assesses the broader value of a third level education qualification beyond economic outcomes.

In Ireland, higher education has been linked with economic development since the 1960s, with the publication of the Investment in Education report. This link between education and the economy can often fall under the term of Human Capital, defined as “productive wealth embodied in labour, skills, and knowledge” (OECD, 2001) and it refers to any stock of knowledge or innate/acquired characteristics a person has that contributes to his or her economic productivity (Garibaldi, 2006).

This chapter collates the available research and data on broader outcomes from higher education beyond employment and salaries. These areas include:

This section considers the impact of a third level education on trust in civic institutions, political engagement, and engagement with public policy.

Table 1 below outlines the level of trust in various civic groups and organisations by level of education. The respondents are split between those with lower than a third level bachelor degree education and those with a third level bachelor degree or higher. Each respondent was asked to rate each group from 1 – 10 with 1 not trusting and 10 fully trusting. Background notes on the CSO Trust Survey can be found in references below. For each grouping excluding the Gardaí and local Government, the higher educated group had more trust than their lower educated peers.

Table 1: Trust in Civic Groups and Organisations by levels of Education

| Don’t trust (0-4) | Neutral (5) | Trust (6-10) | ||||

| Lower than 3rd level Bachelor | 3rd level bachelor or greater | Lower than 3rd level Bachelor | 3rd level bachelor or greater | Lower than 3rd level Bachelor | 3rd level bachelor or greater | |

| Most people | 7% | 5% | 31% | 12% | 61% | 83% |

| National government (the Taoiseach and government ministers) | 37% | 33% | 19% | 14% | 44% | 53% |

| Political parties | 53% | 54% | 23% | 20% | 23% | 25% |

| The civil service | 21% | 19% | 14% | 11% | 64% | 69% |

| The courts and legal system | 23% | 15% | 16% | 12% | 58% | 71% |

| The news media | 40% | 37% | 24% | 18% | 33% | 44% |

| The police (the Gardai) | 11% | 13% | 14% | 11% | 75% | 75% |

| Their local government (local authority) | 34% | 36% | 19% | 18% | 46% | 45% |

Source: CSO 2016

Turning to international data, Milligan et al. (2004) used Eurobarometer data to assess attitudes of UK citizens towards politics and political participation. They analysed 50 questions about whether respondents discuss politics, try to persuade people of their views, and consider themselves politically active. They found strong effects of schooling on all these variables. For example, those compelled to take an extra year of school are about seven percentage points more likely to report they try to persuade others to share their views, six percentage points more likely to frequently discuss political matters with friends, and three percentage points more likely to consider themselves politically active. These results suggest that education improves participation not only as measured by voter turnout, but also in broader measures.

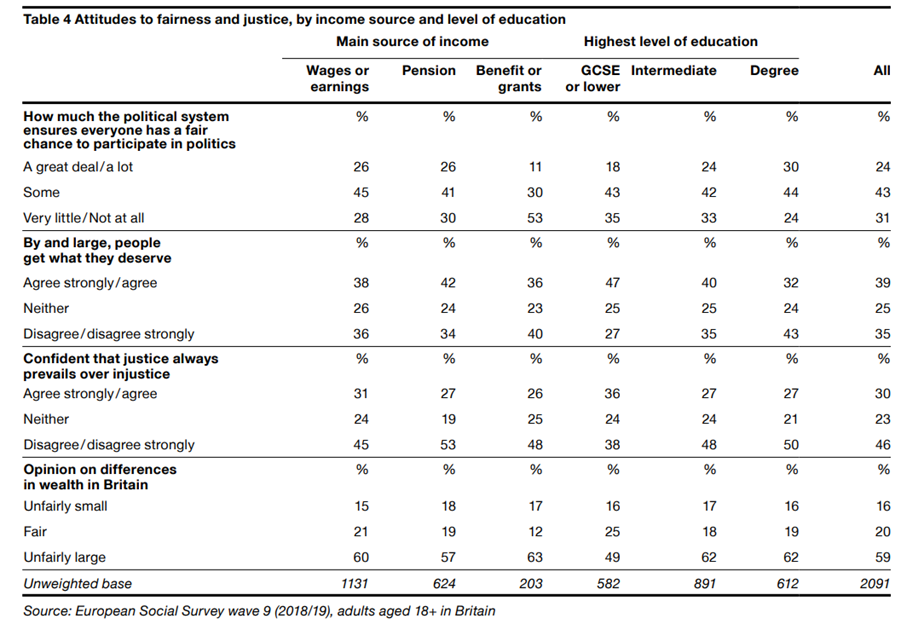

The British Social Attitudes survey tracks changes in people’s social, political, and moral attitudes in Britain, surveying approximately 3,000 people annually each year. Table 2 shows attitudes to fairness and justice, by income source and level of education. It broadly aligns with Irish data presented above and finds that higher levels of education suggest more trust in the political system and more equal political participation. It also suggests that those with third level education are more critical about economic fairness and general ideas of justice.

Table 2: Attitudes to fairness and justice, by income source and level of education

In Britain, education levels can be seen as a dividing line for a range of political and social attitudes and behaviours. Having a degree is strongly associated with more positive attitudes towards immigration, concern for the environment and support for welfare benefits as well as greater political activity (Brennan et al, 2015).

Brooks and Abrahams (2018) address the area of political engagement and higher education in a cross-national study comparing Ireland and England. They contend that universities play a crucial role in developing youth political participation. A university campus can bring together enough like-minded people to enable political networks to form, and also provide resources such as meeting rooms and materials to enable campaigning. Furthermore, Brooks and Abrahams (pg. 112, 2018) found that “students in both countries [England and Ireland] spoke of the liberalising and politicising effect of university… through a process of mixing with people from a variety of backgrounds… opening their minds to different issues.” Their study highlights how students see themselves ‘as an educated group and as such a resource for society and their communities’ (Brooks and Abrahams, pg. 13, 2018).

As well as increasing political engagement, higher education also plays an important role in public policy formation. The recent Covid-19 pandemic illustrated the need to have skilled researchers available to policymakers to discuss problems of national importance and assist in solving such problems. For example, the Expert Advisory Research Subgroup to NPHET was vital to inform NPHET of the emerging research being undertaken to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and also to provide advice on collaborative opportunities to advance COVID-19 research. The Research for Public Policy Roadmap report by the Royal Irish Academy and Irish Research Council further outlines the importance of a strong academic research base to inform policy on a number of challenges such as climate change, cyber-security etc. that Ireland is currently facing. The foundation of a researcher’s expertise, knowledge and skills that will be utilised in addressing national and global challenges has been forged in HEIs throughout their doctoral education and the benefits of this expertise has not only personal benefits but also wider societal benefits too.

The important role that doctoral degree holders have to play in society has also been discussed in a survey undertaken by the Academy of Finland. In the survey, it is suggested that the research skills developed by researchers in HEIs can be used to help improve the effectiveness of their working environments, produce knowledge to aid decision-making around policy and enhance people’s knowledge of the surrounding world. In their conclusions about the survey, it was made clear the cumulative impact that doctoral degree holders have on society: “Doctoral degree holders and their expert communities do have an impact on society. While the added value of the actions of an individual doctoral degree holder for society may not be significant, the cumulative added value of research and research-based expertise is. These skilled experts influence how we interpret the surrounding world and affect decision-making, practice development and the development of new products and innovations, among other things.”

The OECD’s annual Education at a Glance main findings across the OECD on the social outcomes of participating in Higher Education include:

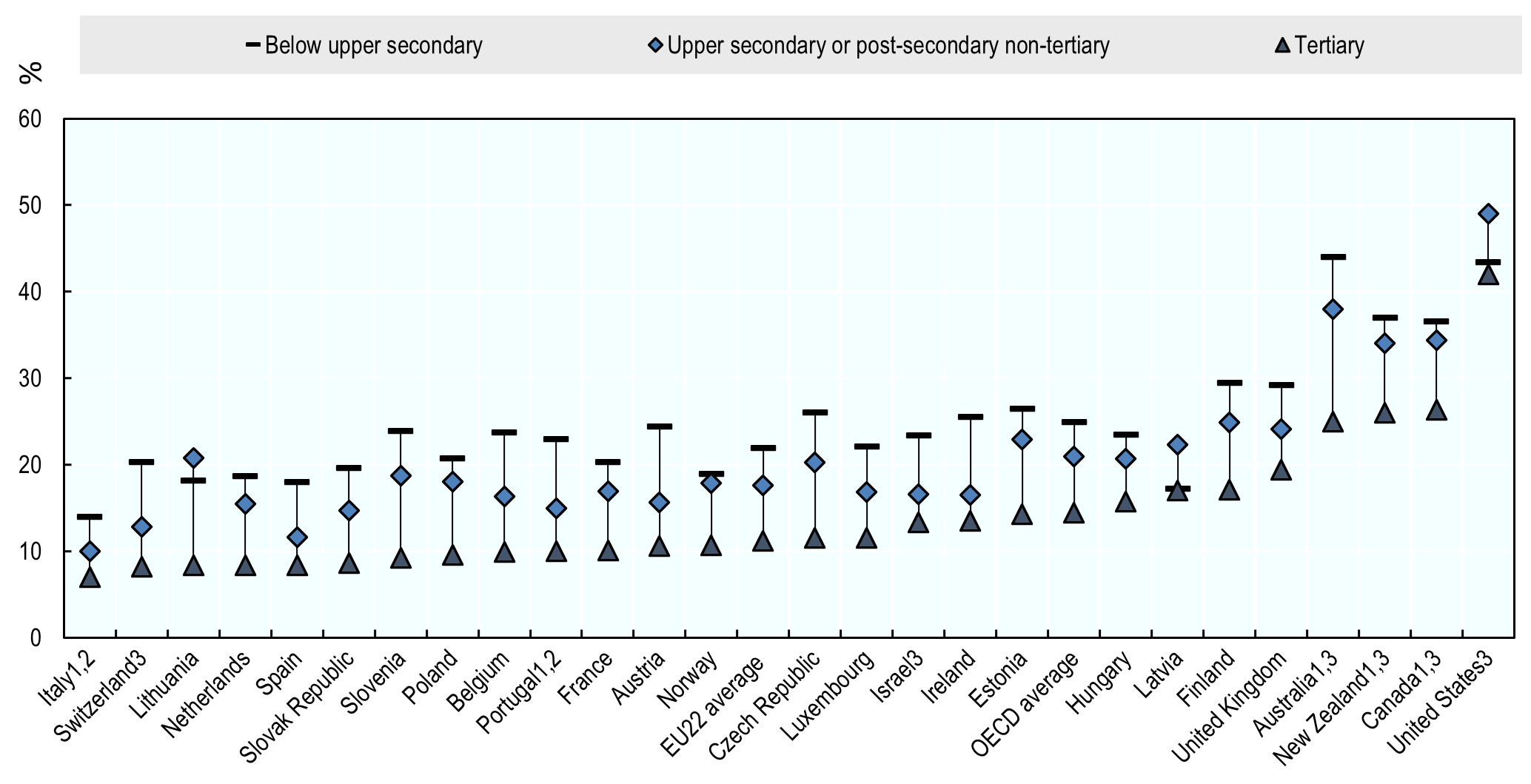

Chart 1 below shows the proportion of adults with obesity by educational attainment across OECD countries. Ireland is above the EU22 average but below the OECD average by tertiary education attainment.

Chart 1: Proportion of adults with obesity, by educational attainment (2017)

Source: OECD Education at a Glance 2021 – Original data source: European Union Survey on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) ad hoc module “Health and children’s health” or national surveys, 25–64-year-olds. *Countries are ranked in ascending order of the percentage of tertiary-educated 25–64-year-olds having a Body Mass Index above 30 kg/m2

This section considers the impact on children of parents with different levels of education, and the link between educational attainment and childcare choices.

Considering the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), studies from Vazquez-Cano et al. (2020) demonstrate that the most important indicator of a child’s reading level is their mother’s education level, profession and level of interest shown in the child’s schoolwork by their mother. Other studies have demonstrated the importance of parental education levels on students’ PISA reading performance scores. Vazquez-Cano et al. (2020) conducted a study on socio-family context and its influence on students’ PISA reading performance scores across three countries in three continents. Their investigation set out to analyse the relationship between parents’ academic qualifications, profession, and role in educating their children and their children’s level of efficacy in reading at the end of the adolescent stage. It does so in three states within different socio-cultural contexts, namely Canada, Finland, and Singapore. The results showed that parents’ academic qualifications, profession and educational role are the most influential aspect of the predictability in the variability of their children’s reading skills. Parents with a low level of education predict poor student reading ability, but when the mother has a medium or high level of education, the results of the students are better than when that level is only achieved by the father. Therefore, the educational role of mothers and fathers, as shown by the interest they take in their children’s schoolwork, is a predictor of students’ reading skills, regardless of the socio-cultural and academic context of the students.

Parental level of education is also found to be a determining factor in students’ academic achievement. A longitudinal study by Duncan and Brooks-Gunn (1997) concluded that a mother’s level of education was significantly related to her children’s academic performance, after controlling for various family socio-economic status factors. Vazquez-Cano found that 41% of students in Finland state that they read for pleasure and only 22% say that they feel obliged to pick up a book. They argue that schools could contribute, as educational organizations and their standing in the community, by identifying family situations that could prejudice a student’s performance.

There have been many instances where education is framed in economic terms such as poverty alleviation, future earnings, and social mobility. Shaw’s (2013) UK study of female students found that ‘where students’ families have little or no experience of higher education their view of it is largely economic, as a route to a better job and greater financial prosperity. This view is continually reinforced by government’ (Shaw, 2013:205). O’Shea, Stone, Delahunty and May (2016) studied students in Australia who were first in their family to access higher education, and also found that discourses of opportunity and betterment dominated, and a view that university is a means to social status and a route out of poverty. O’Shea et al (2016:1026) also identified a further motivating force in that students were aware they were realising the ambitions and dreams of their parents and grandparents. This signals a perception of higher education as the best hope for a brighter future. O’Shea et al (2016) argue that the dominance of discourses of betterment serve to eclipse other important attributes acquired from the university experience, such as self-efficacy, confidence levels, and heightened engagement in other spheres such as social and cultural. They point to the marketing strategies of higher education institutions that invariably focus on students’ successful future selves, which connects this future to attendance at higher education, further propagating the belief that higher education is about economic betterment and disregarding any sense of inherent satisfaction in the learning journey (O’Shea et al, 2016:1031).

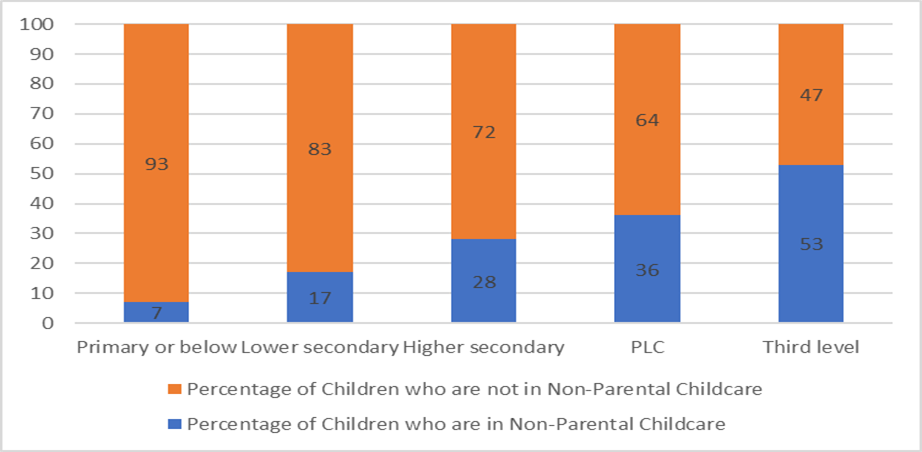

Turning to childcare, Chart 2 below shows CSO data on parental and non-parental childcare from 2016, considering percentage of children between the ages of 0-12 who are in (and not in) non-parental childcare by highest level of maternal education. It shows that as a mother’s level of education rises a higher proportion of children are in non-parental childcare.

Chart 2: Percentage of Children aged 0-12 in Non-Parental Childcare by Maternal level of Education in 2016

Source: CSO, 2016

The wider societal benefits from higher education have a national importance. In Impact 2030: Ireland’s Research and Innovation Strategy and the Innovate for Ireland initiative the need for a strong research talent pipeline is highlighted as a necessity to address national and global grand challenges. Doctoral graduates are the researchers of the future needed to address these challenges; HEIs will facilitate this need by producing doctoral graduates with the necessary skills and knowledge to reach their potential. The EUA Council for Doctoral Education in its leaflet on why Doctoral Education matters for Europe also outlines how “by generating knowledge and scientific and technological breakthroughs, universities play a crucial role in advancing European societies” and how doctoral education is vital in connecting higher education, innovative research and society.

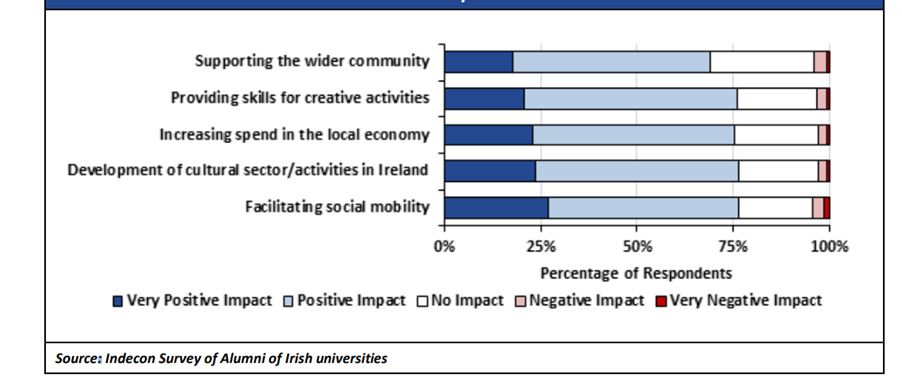

In 2019 Indecon assessed the economic and social impact of the Irish Universities sector and included a focus on the social and cultural impacts of the sector, with data provided on the views of alumni on the social, cultural and community outcomes of higher education via a survey. Key findings from the survey are outlined below and in Chart 3. Over 75% of respondents said that Irish universities had either a very positive or positive impact on the following areas:

Chart 3: Views of Alumni on the Impact of University Education on Social, Cultural and Community Outcomes

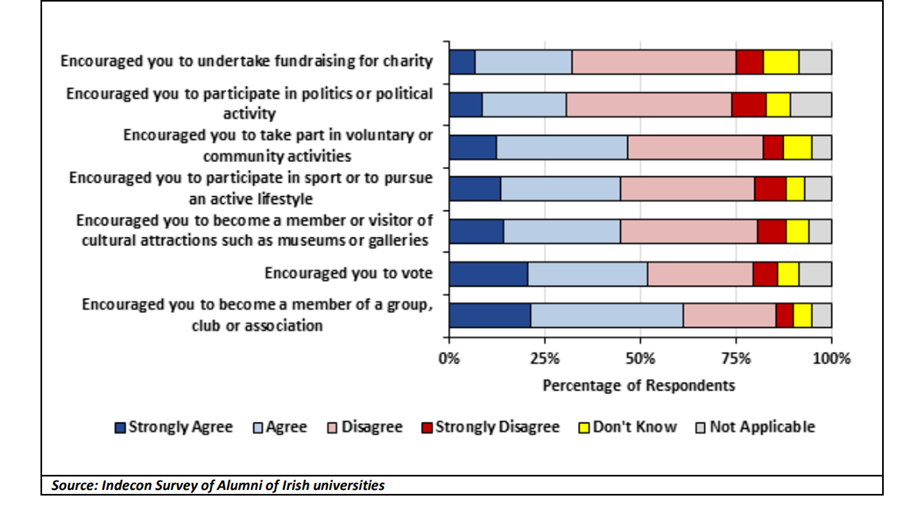

The report also discussed the levels of social engagement by Irish universities, their students, and staff, and presented the views of alumni on the impact of university education on personal development and in their wider contribution to society. Chart 4 highlights the impact of a university education on personal development. Over 60% of respondents were encouraged to become a member of a group, club or association, c. 50% encouraged to vote and take part in voluntary or community activities and pursue a sport or active lifestyle.

Chart 4: Views of Alumni on the impact of University Education on Personal Development

Averill (2019) conducted a report for National University of Ireland which focused on exploring and examining the perceived non-economic outcomes of mass participation in the traditional university sector. Within her work she analysed the 2019 Indecon Assessment of the Economic and Social Impact of Irish Universities and concluded that it focused primarily on the economic outcomes of university. According to Averill (2019) a non-economic area assessed in the report – the benefit to society from volunteering – was reported in economic terms as it was expressed in terms of Euro value of unpaid work rather than the non-material benefit of the work for the community. Social mobility was also addressed, and the report stated that 15% of those who accessed university in 2017 came from disadvantaged backgrounds. However, the report did not include a measurement of the outcomes of university education for these students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The report addressed the public good aspect directly in terms of social and cultural contributions of universities, reporting that universities prepare a cohort of people who become significant in the arts, both as artists and in promoting the arts. This was assessed in a quantitative way, measuring footfall at events. For example, it highlights attractions such as the Helix Theatre at DCU, and the Book of Kells at Trinity College Dublin. Regarding the Book of Kells, this and other illuminated manuscripts are highly valued as priceless art and religious texts, by a broad school of academics and the public with interests in religion, art history and medieval history, and would draw crowds regardless of their location. Furthermore, Averill argued, that it should be acknowledged that Trinity College Dublin and other centres of learning have played an important role in preserving such artefacts, thereby contributing to the public good. Averill also noted an important finding in the Indecon report, that 45% of respondents indicated that they were encouraged to engage politically.

Increased resilience is a reported benefit to students who have graduated from higher education courses; in particular PhD courses, which require grit and perseverance to complete. A 2014 report by CFE Research in the UK entitled “The impact of doctoral careers” outlines how resilience built in doctoral graduates throughout their studies had “resulted in them feeling better able to handle the challenges they face in their day-today lives” while also improving their problem-solving skills and self-belief to tackle different issues outside of their workplace.

Campus Engage is a national initiative which works with 17 higher education institutions to enable and embed civic and community engagement activity across campuses and communities in Ireland. Their 2018 report showcased case studies of voluntary work taken around Ireland which promoted community-service, social justice, diversity, empathy, and social responsibility. Examples included DIT (now TU Dublin City) students’ community-based research informing Irish penal system policy and practice and the FoodCloud initiative (TCD), which aimed to reduced food waste, reduce food poverty, and benefit 40 Dublin city centre charities. These demonstrate that skills and interests developed from participation in higher education can lead to broader societal outcomes.

Finally, the CSO explored the link between crime and education in the 2016 census and found that 57% of prisoners in Ireland had an education level of Junior Cert or below. Hughes (2021) found that prisoners are one of the most socially and economically disadvantaged groups in society, with low levels of educational attainment and involvement in higher education. She also discussed the transformative nature of education and learning by explaining that: “Higher Education has many advantages for prisoners and former prisoners, providing opportunities to develop new skills, self-respect, resilience, and it can also assist in the development of a new identity as a non-offender, and the sense of a new life and how it can be realised. This new identity is an essential feature in desistance from crime and developing a life that is crime free, with new opportunities based on educational achievements, rather than criminal opportunities.”

This chapter has set out findings from national and international reports that consider graduate outcomes that extend beyond employability and the labour market. Research indicates that there are both individual and societal benefits to higher education attainment, and that these persist and extend into future generations.

Graduates of higher education tend to have a higher level of trust in public institutions; are more likely to vote; and have a greater awareness of, and sense of responsibility towards, social justice. They are also more likely to live longer and experience obesity less than those with lower levels of education. Maternal education levels have a significant impact on the educational outcomes of children, with higher educational attainment of mothers associated with superior child literacy and educational outcomes. Research has also found that higher levels of education attainment have a broader societal impact, ensuring that Ireland can meet global challenges.

Averill, A. (2021). The Contribution of Mass Higher Education in Ireland to the Public Good. http://www.nui.ie/publications/docs/2021/NUI_Discussion_Paper_No2.pdf

Brennan, J. et al (2015). The effect of Higher Education on graduates’ attitudes: Secondary Analysis of the British Social Attitudes Survey. BIS Research Paper No. 200 Department for Business, Innovation and Skills

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. J. (1997). The effects of poverty on children. The future of children, 55-71.

Brooks, R., & Abrahams, J. (2018). Higher education students as consumers? Evidence from England. In A. Tarabini, & N. Ingram (Eds.), Educational choices, transitions, and aspirations in Europe: systematic, institutional, and subjective challenges (1 ed., pp. 185- 193). (Routledge Research in International and Comparative Education). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315102368

Campus Engage (2018). Campus Engage World Café, National Consultation Report, 2014.

Central Statistics Office (2016). Percentage of Children in Non-Parental Childcare. Updated 2020.

https://data.gov.ie/dataset/cca07-percentage-of-children-in-non-parental-childcare

Central Statistics Office (2021). Trust Survey, December 2021: A CSO Frontier Output. Retrieved https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/fp/fptrus/trustsurveydecember2021/backgroundnotes/

CFE Research (2014). The impact of doctoral careers. CFE Research, United Kingdom. https://www.ncub.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Impact-1.pdf

Department for Business, Innovation & Skills (2015). The effect of Higher Education on graduates’ attitudes: Secondary Analysis of the British Social Attitudes Survey. United Kingdom.

Department of Further and Higher Education, Research, Innovation and Science. (2021). Impact 2030: Ireland’s Research and Innovation Strategy. Dublin, Ireland.

Department of Further and Higher Education, Research, Innovation and Science. (2022). Innovate for Ireland Press Release. https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/1b902-taoiseach-and-minister-harris-announce-innovate-for-ireland-a-new-initiative-to-recruit-and-retain-talent/

Department of Health (2020). National Public Health Emergency Team (NPHET) for COVID-19 Governance Structures. Ireland.

Doyle, M., Riordan, S. & Carey, D. (2021) Research for Public Policy: An Outline Roadmap. Royal Irish Academy.

EUA Council for Doctoral Education (2018). Doctoral Education: Why it matters for Europe. Geneva, Switzerland.

Garibaldi, Pietro, (2006), Personnel Economics in Imperfect Labour Markets, Oxford University Press.

https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:oxp:obooks:9780199280674.

Hughes, N (2021) “Higher Education and Desistance From Crime,” Irish Journal of Academic Practice: 9:1, Article 3. Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijap/vol9/iss1/3

Indecon (2019). Indecon Independent Assessment Of The Economic And Social Impact Of Irish Universities. Retrieved https://www.iua.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Indecon-Independent-Assessment-of-the-Economic-and-Social-Impact-of-the-Irish-Universities_full-report-4.4.19.pdf

Milligan, K., & Moretti, E., & Oreopoulos, P. (2003). Does Education Improve Citizenship? Evidence from the U.S. and the U.K. Journal of Public Economics. 88.

OECD (2001), The Well-being of Nations: The Role of Human and Social Capital, OECD Publishing, Paris,

https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264189515-en.

OECD (2021). Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators. OECD.

O’Shea, S., Stone, C., Delahunty, J. & May, J. (2016). Discourses of betterment and opportunity: Exploring the privileging of university attendance for first-in-family learners. Studies in Higher Education, Online First 1-19.

Shaw, A. (2013). Family fortunes: Female students’ perceptions and expectations of higher education and an examination of how they, and their parents, see the benefits of university. Educational studies, 39(2), 195-207.

Tornroos, J. (2017). The Role of Doctoral Degree Holders in Society. Academy of Finland.

Vázquez-Cano, E., De la Calle-Cabrera, A. M., Hervás-Gómez, C., & López-Meneses, E. (2020). Socio-family context and its influence on students’ PISA reading performance scores: Evidence from three countries in three continents. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 20(2), 50 – 62. http://dx.doi.org/10.12738/jestp.2020.2.004